The story of one man’s call for justice that moved the whole nation

Two weeks after the prison death of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, one of Tibet’s most well-known political prisoners, another renowned political prisoner has been released after serving a sentence of 8 years. The Chinese authorities avoided his receiving a hero’s welcome home by driving him straight to his house from prison at one o’clock in the morning on Friday. But within hours, news of his release had reached the outside world, causing celebrations in Tibetan communities across the world. The reason for the rejoicing lies in the fact that the released political prisoner may have single handedly affected the consciousness and self-identity of all Tibetans today, and impacted the course of events in Tibet over the last 8 years.

For Tibetans who’ve lived through the political upheavals and repressive crackdowns that rocked Tibet over the last few years, 2007 is a year that feels remotely distant and almost of another era.

Since the historic 1989 protests that took place in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, which was put down with violence and the sweeping punishment that touched the lives of thousands of Tibetans, Tibet had remained under tight control of Chinese security forces, with only small protests and individual expressions of dissent taking place for almost 20 years. The period saw a progressive hardening of policies governing Tibetan religion and culture, and of individual freedoms, along with the escalation of largescale and exploitative use of Tibetan land, attacks against the Dalai Lama, and for the first time since the 1960s, the extension of the repressive policies governing the Tibet Autonomous Region to all Tibetan autonomous areas in neighboring Chinese provinces.

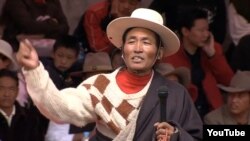

Then in 2007, Rungye Adak spoke openly from the stage at a horse festival. His speech shook the audience of thousands, and acted like a signal arrow in the night sky for Tibetans who had been silenced through fear and intimidation for almost twenty years.

Adak was not an angry young activist, or a dissident intellectual, and nor was he a desperate monk from a monastery under siege by the thought police. He was a middle aged rural pastoralist with several children, and a man who was respected in his conservative nomadic community.

But on August 1, 2007, at the Lithang (Chinese: Litang) horse festival, one of Tibet’s largest such social gatherings which had only recently been allowed to convene after years of being banned by the Chinese, Rungye Adak stepped onto the stage in a calm and collected manner, offered a Khatag (a white silk greeting scarf) to the head of the local monastery, the Lithang Kyabgon, and then took the microphone. He spoke eloquently on the suffering of Tibetans under Chinese rule, called for the release of political prisoners, and finally, expressed his desire for the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet.

Adak didn’t appear angry or agitated as he spoke, as one might have been from knowing what the consequences would be for speaking out in Tibet. In fact if one weren’t listening carefully to his words, Atak looked as if he could have been reciting poetry or praising the gathering of thousands under the azure blue Tibetan sky. And when you look at the video of him on the stage, with local communist bosses seated in front of a crowd of thousands, it is apparent that it takes a prolonged period of time for his words to be processed by the security police, and for them to take action by taking him away.

Adak’s detention was followed by protests and petitions by hundreds of Tibetans in Lithang who demanded his release, insisting that he had not transgressed any Chinese laws. Word coming out of Tibet at the time suggested that Rungye Adak’s speech may have been prompted by a provocative Chinese initiative in local monasteries at the time which required monks to sign documents stating that they were against the Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet.

Word of Rungye Adak’s speech spread quickly across Tibet, as did the news that he was charged with ‘provocation to subvert state power’ and sentenced to 8 years in prison. Adak's nephew, Adak Lopoe, was sentenced to ten years, and a local teacher named Kunkhyen was given a nine year sentence, both for trying to inform the outside world about Rungye Adak's protest plea, which was seen by the Chinese courts as a crime against national security.

Nothing major happened for seven months following Adak’s speech. Tibetans were accustomed to incidences of dissent and crackdowns occurring from time to time. But Atak’s bold and clear eyed words, heroic to almost every Tibetan who heard them, had touched a nerve. Like the spark from a flint lighter on a moonless night, it caused millions of Tibetans to see their situation in one bright and fiery instance, and made them conscious of the decades of pent up frustration and anger within them.

And then in March 2008, once again started by provocative police action against monks in Lhasa, the city erupted in the largest mass uprising since 1959, which soon spread across the Tibetan region, an area the size of Western Europe. Street demonstrations, protests in monasteries and temples, and assaults on Chinese flags on official buildings swept the Tibetan plateau. China responded with mass killings of demonstrators, lockdowns and forced reeducation campaigns in monasteries, and the arrests, torture, and mistreatment of thousands of Tibetans. There were stories told in hushed tones of the mass burnings of killed protesters in Lhasa, amongst who were seen injured but live people.

For a year, the entire Tibetan region was under heavy lockdown as the Chinese security and armed police hunted down individuals and raided communities, imprisoning countless people and torturing them into admitting that the Dalai Lama and hostile foreign anti-China forces had instigated the Lhasa protest. The fact that Tibetans were suffering under Chinese rule and Chinese policies governing Tibetan culture, religion, and economy as expressed by Rungye Adak and as was conveyed by the nationwide protests of 2008 was ignored by the Chinese leaders, both locally and in Beijing.

And then on February 27, 2009, a young monk named Tapey burnt himself to protest the repression and violence that the Chinese were inflicting on his monastery and his community. Tibetan writer Woeser in writing about monk Tapey’s self-immolation, says that, ‘The reasons for his action lie in protests that erupted in 2008; Ngaba Prefecture in Amdo was suppressed in a bloody and violent way by local authorities, affecting a pregnant woman and a 5-year-old child and resulting in over twenty 16-year-old female middle school pupils being shot dead. What is more, a year later on the third day of the Tibetan New Year, the mourning ceremony for the departed spirits was cancelled; this is when Tapey left Kirti Monastery, ran into the streets and lit his gasoline-soaked robes. From within the flames he held up the Tibetan flag and a photograph of His Holiness the Dalai Lama; then he was shot by military police.” Others have suggested that Tapey’s protest may also have been driven by the abuse and humiliation being directed at his teachers and senior monks at his monastery who were being punished for not denouncing their spiritual head and the Dalai Lama.

Since Tapey’s self-immolation of 2009, over 140 more Tibetan men, women and children have burnt themselves to protest Chinese repression in Tibet, most of who have died. In almost all cases, reports have emerged afterwards stating that the individuals were almost invariably empathetic and public spirited people who were deeply moved by the plight of either their own communities or Tibet and the Tibetan people in general. China’s official response to the self-immolations in Tibet has been almost identical to its response to Rungye Adak’s speech. Rather than investigating each case and seeking to understand the grievances that drive someone to burn themselves, the self-immolation protesters were accused of crimes against national security, labelled as fringe individuals, and their relatives and friends charged and sentenced as accomplices.

Exactly eight years after Rungye Adak took to the stage at the horse festival in Lithang, China appears to still be guided by the very same policies that he spoke to in his speech. In a possible sign that the ruling Chinese Communist party does not have any new ideas for resolving the Tibetan situation, a Politburo level meeting in Beijing on July 30 pledged to take steps for tackling instability in Tibet and containing "anti-separatism battle," and hardened its position on the Dalai Lama, saying that the CPC’s consent is necessary in the selection and appointment of his reincarnation.

However while the thinking in Beijing may not have changed very much since 2007, Rungye Adak’s wake up call to the Tibetan people has forever changed the way Tibetans see themselves and their situation under Chinese rule. The events that have unfolded in Tibet since Adak’s speech indicate that Tibetans are today fully cognizant of what China is doing to their land and lives, and that the microphones on makeshift stages across Tibet are not just for party use.